Introduction to Coding

Writing code is not trivial, and I cannot hope to make you an expert here. However, it is not as difficult as you might think, and hopefully this will get you started.

Quest uses four languages, including XML. If you click on Tools - Code view you will see the XML. Writing XML is a pain in the neck; let Quest do that for you. The only time I ever look at this code view is when I have spotted a typo when playing my game and want to quickly find it to correct it.

Quest also uses Javascript, but unless you want to do fancy stuff with the interface, you can ignore that. This is not about JavaScript.

Quest is written in C#, but you will never need to know anything about C# to create games.

The important one is the one used in scripts, ASL, and that is unique to Quest. It is kind of similar to C++/Java and many of the built-in functions come from Visual BASIC.

A Note About Objects

Note: The word “object” has two distinct meanings in Quest. Firstly it can mean something that the player can interact with, perhaps pick up, examine, etc. However, in the programming world, an object is sort of data structure, and in that sense Quest uses it to include rooms, exits, commands, the game object and indeed everything in the game world. When I use the word “object”, I mean it in this second sense. I will use the word “item” to indicate the first meaning (however, if I am quoting a label or dialogue box, “object” will probably mean item).

Code view versus the GUI

I am going to assume you have made it to the end of the tutorial, and now you are ready to jump into the deep end!

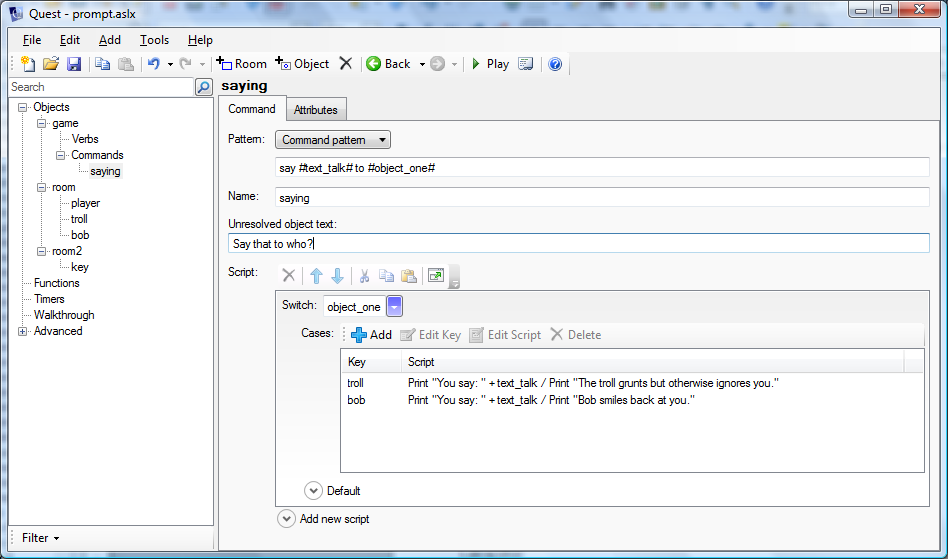

Well, the first thing to say is you are already splashing around in the shallow end. If you completed the tutorial, you have already written code! Let us take a look at the “saying” command. This is the script:

What you are looking at is a graphical representation of Quest code. Click on the “Code view” button (in the desktop version, this is icon that looks like the </>; it has changed since the image above)…

switch (object_one) {

case (troll) {

msg ("You say: " + text_talk)

msg ("The troll grunts but otherwise ignores you.")

}

case (bob) {

msg ("You say: " + text_talk)

msg ("Bob smiles back at you.")

}

default {

msg ("You say: " + text_talk + " but the " + object_one.name + " says nothing, possible because, you know, it cannot speak.")

}

}

… And you will see code behind. Code you wrote! And if you compare the two, you will see how the lines match up. At the top is the switch line, and below that each of the case lines.

Some people prefer to type the code, some prefer to use the GUI, it does not particularly matter, because anything written in code can be seen in the GUI, and anything created with the GUI can be seen in code.

So why use code?

Code has a number of advantages, but one of the most important is that you can easily copy-and-paste into a forum post if you are having a problem, and you can easily copy-and-paste into your game from someone else’s forum post or one of these help files.

So why use the GUI?

The GUI is excellent when you start out because it handles the details (those { and } that have to be just right, for example), and also it is far easier selecting a function from a menu instead of trying to remember its name - and exactly how it is written (but note that there are many functions that are not in the lists).

So which should I use?

Start with the GUI, but take a look at the code you are creating to see how it looks and get an idea of how it works. As you get more confident, and your scripts get more complicated, see if you can start to use code.

Scripts in Quest

Scripts are found in numerous places in Quest. Functions and commands are little more than scripts, but you can also attach scripts to items, rooms and exits. Rooms can be set to run a script when the player enters or leaves. Verbs on objects are all scripts, exits can run a script when used, items can run a script when picked up or dropped.

Here is an example from a built-in command, INVENTORY:

list = FormatObjectList(Template("CarryingListHeader"), game.pov, Template("And"), ".")

if (list = "") {

msg (Template("NotCarryingAnything"))

}

else {

msg (list)

}

At its simplest, code is a list of instructions. When the script starts (the player enters the room, drops the item, or whatever), Quest starts at the top and does each line in turn - just like following a recipe when baking a cake.

Here is a simple example that might be set on an exit:

msg("You crawl for some time through the dark tunnel, before arriving at...")

player.parent = this.to

Quest does the first line, which prints out the message, then the second line, which moves the player. Let’s look at the second line in more detail…

Attributes

Objects have attributes, which are values with names. You can set these up on the Attributes tab for any object (if off-line), but everything you set on the other tabs is an attribute too, with a pre-defined name. An attribute can be a string, an integer, another object or a script and more besides.

In code, you can access an attribute using the dot operator. The above example accesses the “parent” attribute of the player object and the “to” attribute of “this”.

What is “this”?

In Quest code, “this” has a special meaning, it refers to the object that this script belongs to. In the example, then, “this” refers to the exit itself. I could have used the name of the exit instead, but generally it is better to use “this”, as it allows your code to be reused more easily.

What is “to”?

All exits have a “to” attribute which is an object (or technically a pointer to an object); the destination of the exit, so “this.to” is the destination of the exit the script is attached to.

What is “parent”

All items and exits have a “parent” attribute (rooms can too). It indicates the object’s position in the hierarchy in the left pane, or who the object belongs to. Any item that belongs to the player is in the player’s inventory; it has the player as its parent. Any item or exit in a room has that room as the parent, and similarly if the player has a room as its parent, then the player is in that room. Any item that has another item as its parent is inside that object (though you need to set up the latter as a container for that to work properly).

To move the player to a new room, all you have to do is set the player’s parent to the new room. This is what the script above does. It sets the player’s parent to be whatever room is indicated by the “to” attribute of this exit.

To move an item to the player, set the item’s parent to the player.

my_item.parent = player

To move an item to the current room, set its parent to the player’s parent

my_item.parent = player.parent

Aside: About “player”

Just be aware that Quest has the capability for changing the point of view (i.e. swapping from one player character to another) built-in. To handle that, Quest has an attribute of the game object called “pov”, and that refers to the current player. To be able to change the player’s point of view, we should use “game.pov” rather than “player”. I mention this for completeness; I am going to continue to use “player” to keep things simple, but if you look at code in a library it will probably use “game.pov”.

Computers are fussy

You have to be precise when writing code. Computers will not cope if you miss a quote or a bracket. To check you have not missed something, always click on the View code icon and check there is no red writing. Scroll down to the bottom to be sure.

Working out what is missing can be tricky! However, if you do not check at this stage, Quest will sometimes try to correct the problem itself, which sometimes means deleting big chunks of code, leaving it in rather more of a mess.

Quotes in strings

Given a double quote terminates a string, how do you handle doubles quotes? This is going to fail:

msg ("The scarecrow looks at you. "Howdy!" he says.")

Quest will consider "The scarecrow looks at you. " to be a string, and " he says." to be another, and will try to work out what Howdy! is supposed to mean! The trick is to use an escape code; put a backslash before the double quotes within the string. This will work fine.

msg ("The scarecrow looks at you. \"Howdy!\" he says.")

If you want to put a backslash into a string, you need to escape that too, so use \\.

Functions

Quest has a large number of script commands and functions, listed on these helpful pages:

See here for how to use them and how to write your own:

Control Structures

A control structure allows code to break out of the simple recipe. Instead of just doing each line in turn, we can get Quest to perform some lines repeatedly or to only do certain lines if specific conditions are met.

Control structures have the same general format. First there is the script command, then the values, then the instructions. The values all go inside a set of brackets, and separated by commas. The instructions all go on separate lines (just like normal code), and inside a set of curly braces. To help make it easier to read, the instructions are indented. Quest will do this for you, but I recommend getting in the habit of doing it yourself anyway.

Let us have a look at a couple:

The foreach Loop

This is how to go through each entry in a list (or dictionary). Quest has a number of “scope” functions that will grab all the appropriate items. For example, ScopeInventory gives us a list of items in the player’s inventory. We can use that with foreach.

foreach (item, ScopeInventory()) {

msg("You dry out " + GetDisplayName(item))

item.wet = false

}

The first thing is the script command, foreach. Next we have the values, and these are inside brackets, separated by commas. In this case, the first is a variable that we can use in the code section. The second is the list, which we are getting from ScopeInventory.

Then there are the instructions. Here there are two, each on its own line, indented by two spaces. They are surrounded by curly braces.

Quest will go though the objects returned by ScopeInventory. For each one, it will put the value in “item” and then run the code.

The if Structure

You use if to make the script sometimes do one thing and sometimes another. In this simple example, the message is only seen if the hat item is in this room.

if (hat.parent = this) {

msg("There is a bowler hat on the hatstand.")

}

You can add an else if you want; this will get done if the condition fails:

if (hat.parent = this) {

msg("There is a bowler hat on the hatstand.")

}

else {

msg("The hatstand is devoid of hats.")

}

You can append an if to an else, to make complex structures. In an adventure game, a common use is to check all the conditions have been met before something happens. This example might be the script for a SIT command.

if (not this.has_chair) {

msg("There's nowhere to sit here!")

}

else if (not player.parent.name = clown_room) {

msg("Okay, you sit down. Now what?")

}

else if (not hat.worn) {

msg ("You sit on the orange chair. A clown suddenly appears in the room, looks at your head in confusion, then disappears as quickly.")

}

else if (clown.parent = clown_room) {

msg("You are already sat down.")

}

else {

msg ("You sit on the orange chair. A clown suddenly appears in the room, and knocks the hat off your head.")

hat.worn = false

hat.parent = clown_room

clown.parent = clown_room

}

The strategy here is to test each condition has not been met in turn, and give a suitable response if it fails. Only if each condition passes do we reach the final “else”, where the player has solved the puzzle and the game world gets updated.

Complex conditions

You can do some complicated condition testing in Quest. To test if conditions are all true, use the and operator, and to test if at least one is true, use or. You can also test a condition is not true using not. In this example all the above conditions are checked at once (the first implicitly).

if (player.parent.name = clown_room and hat.worn and not clown.parent = clown_room) {

msg ("You sit on the orange chair. A clown suddenly appears in the room, and knocks the hat off your head.")

}

else {

msg("Nothing happens.")

}

That said, the if/if else/else sequence described before is to be preferred as it gives the player more information, and is a lot easier you you, the creator, to see what is going on.